Sarah Helen Power Whitman (1803-1878) was born in her grandfather’s house in Providence at 10:00 in the evening on January 19, exactly six years before the birth of her future suitor, Edgar Allan Poe. She was the second surviving child of Nicholas Power VI and Anna Marsh Power, named after her aunt Sarah Power Williams. Whitman had an older sister, Rebecca, and three younger siblings. Two of those younger siblings died in infancy before her youngest surviving sister, Susan, was born in 1813. Whitman’s first words were “All’s well.”

After the death of her grandfather in 1808, Whitman and her family had moved into various boarding houses throughout Providence. In 1813, her father, Nicholas Power, lost his merchant business from the effects of the War of 1812. He set out to sea to make a living for his family but was captured by a British fleet shortly after his departure. Power was held a prisoner of war by the British, and when his family stopped hearing from him, they presumed he was dead. Anna Power, now listed as “widow” in Providence directories, rented the quaint red home on Benefit Street for her and her three daughters.

The young Sarah Helen Whitman attended Miss Sterry’s school on South Main Street; however, she became somewhat of a delinquent, often skipping school to pursue her own studies. Ironically, this seemed to have a positive effect on her, since she maintained a lofty intelligence that surpassed her peers. Whitman was fluent in multiple foreign languages including Latin, French, and German. Her mother would often read the works of Shakespeare aloud to her and by eight years old, Whitman was reading gothic novels such as Clara Reeves’ The Old English Baron, on her own. As Whitman grew older, she maintained a love of novels and poetry to the dismay of her extended family, who strongly disapproved of it.

In 1824, Sarah Helen Whitman became engaged to a law student attending Brown University named John Winslow Whitman, finally marrying him four years later. The wedding was held at Sarah Helen’s aunt and uncle’s home on Long Island, New York, on July 10, 1828. Her uncle, Cornelius Bogert, gave her away since her father was “dead.” However, unbeknown to his family, Nicholas Power was very much alive. Upon his release from British custody in 1815, Power decided to continue his life at sea without ever notifying his family of his survival. In 1832, nearly nineteen years after his departure from home, he returned to his wife in a bizarre attempt to resume his family life. She did not receive him well, removing her widow’s bonnet and promptly beating him with it until he was forced out of the house. She had nothing to do with him after this, and, naturally, began a fervent distrust of men all together. Sarah Helen Whitman was able to avoid the controversy of her father, having moved to Boston with her husband shortly after their wedding.

Outside of his law practice, John Winslow Whitman was affiliated with a magazine called, The Ladies’ Album, and a newspaper called, The Times. These publications served as an outlet for Sarah Helen Whitman as she began publishing her poetry, essays, and criticism. Boston was a progressive city that introduced her to the social reform movements that she would carry with her for the rest of her life. Abolition, temperance, transcendentalism, and vegetarianism were among those movements.

During their marriage, John Winslow was arrested for writing a bad check. He was held at the Leverett Street prison in Boston and it was at this point in Sarah Helen’s marriage that she may have come to the realization that, like her mother, she married a very impractical man. In the summer of 1830, Sarah Helen and her husband were visiting her family in Providence. On one July evening, John Winslow took a walk with his mother-in-law to the Grotto down by the Moses Brown Bridge. Sarah Helen believed that it was on this walk with her mother that John Winslow caught a cold that would eventually kill him. In 1833, while he was visiting his father in Pembroke, Massachusetts, he died from complications of that lingering illness. Sarah Helen was visiting her mother in Providence at the time, and had not heard of her husband’s death until five days later when William Patten traveled from Pembroke to Providence to tell her the news that she was now a widow. Sarah Helen Whitman could now solidify her place among the female literati, for she had very tragically and poetically lost her husband.

Whitman moved back into her mother’s house and remained in Providence for the rest of her life. However, Whitman continued to write and publish, contributing a number of pieces to the Daily Journal (now known as the Providence Journal) and other publications throughout New England, even while she was under the overbearing and restrictive roof of her mother. Whitman was becoming a fierce activist, rallying for Women’s Suffrage and Abolition. Her literary criticism deemed her one of the earliest female critics in the country. Whitman became well known as a poet, publishing her first volume of poetry titled Hours of Life and Other Poems in 1853. A firm believer in Spiritualism, Whitman frequently attended and even hosted séances throughout her life.

Whitman was a remarkably beautiful woman, not just in the prime of her life, but her whole life. She had deep-set blue eyes that seemed to gaze beyond this world. Her dark brown hair was often tucked behind a veil draped over her head. She always wore short sleeve dresses that were cut below the shoulders, with a shawl wrapped around her head or neck. She claimed that this style was due to her arms and shoulders always being warm, and her head and neck always being cold. She wore white in the summer and black in the winter. She carried herself with charm, often fluttering around Providence like a bird. She was gentle, calm, and often deep in thought. Her intelligence was respected. All who knew her could not help but fall in love with her. She wore a small wooden coffin pendant around her neck that was carved out of a dark wood by one of her friends and pinned to a black satin ribbon. Whitman was enthralled by the macabre, having especially been a fan of Edgar Allan Poe’s works.

In 1845, Poe was in Providence for the first time by the invitation of his friend, Frances Osgood, who was staying in the city at the time. On the evening of Poe’s visit, he took a leisurely walk along Benefit Street with Osgood, likely because she was staying at the Mansion House Hotel, which was located at the corner of South Court and Benefit Street. While walking north from the hotel, they passed by the home of Sarah Helen Whitman. Osgood mentioned her to Poe, and asked if he would like to meet her during his visit to Providence. Poe declined an introduction so adamantly that it provoked Osgood into a quarrel with him. Poe later claimed that the reason he refused to meet Whitman was because he thought she was a married woman.

After Poe walked Osgood back to her hotel, he traveled northbound, the same route from which he had just come. It was a hot and humid night in July. The moon was full (or nearly full), and it was about midnight at this point. While taking in the magnificent views of the city, Poe approached Whitman’s house to find her now outside. She was ethereal-looking as she walked to and from her rose garden in the backyard. She was clad in a white muslin dress, a white shawl, and with a sheer veil draped over her gentle face. Her garments floated in the warm, evening breeze. Poe told Osgood about the encounter the next day, and the sight of Sarah Helen Whitman left a perpetual mark on his mind.

An introduction between the poets was inevitably to come in 1848, after Whitman published a flirtatious Valentine poem in the Home Journal titled “To Edgar A. Poe,” later renamed, “The Raven.” She was completely unaware that Poe already had a slight infatuation with her after seeing her three years prior. Flattered by Whitman’s unsolicited attention, Poe tore out a poem from a published collection of his works that conveniently bore a title with Whitman’s nickname, “To Helen.” Poe sent the poem to her anonymously. Whitman did not reply to the poem, so Poe wrote a tailored poem just for her and sent it anonymously in the hopes that she would connect some dots. The poem, inspired by his first sighting of her, began:

I saw thee once — once only — years ago:

I must not say how many — but not many.

It was a July midnight; and from out

A full-orbed moon, that, like thine own soul, soaring,

Sought a precipitate pathway up through heaven,

There fell a silvery-silken veil of light,

With quietude, and sultriness, and slumber,

Upon the upturn’d faces of a thousand

Roses that grew in an enchanted garden

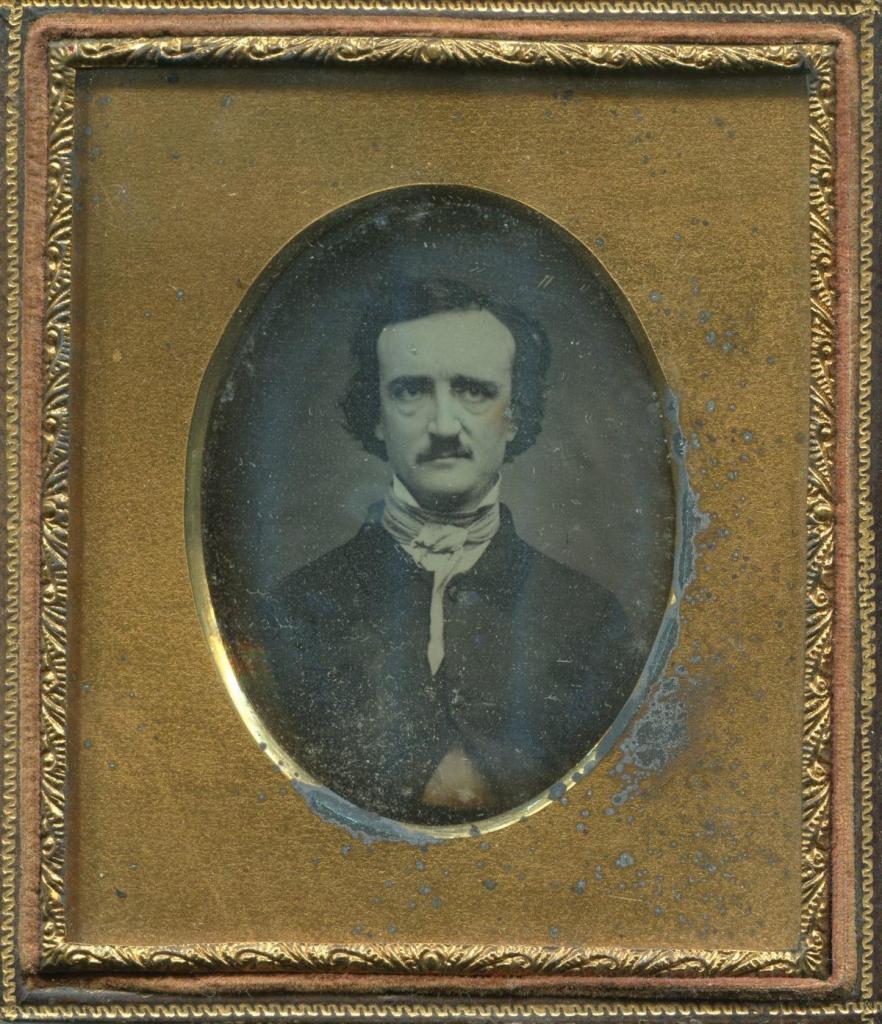

Poe’s next step in securing a meeting with Whitman was cunning, if not bold. He posed as an autograph collector under the pseudonym Edward S. T. Grey, writing in request of her signature. This was a ploy so that she would return his letter and confirm her residency in Providence. Once Poe got the reply, he traveled straight to Providence and called on her at this very house on September 21, 1848. They meet for the very first time. A courtship ensued over the next three months. In this time, Whitman rejected Poe’s constant marriage proposals, spiraling him into a deep depression and hopelessness. Two daguerreotypes were taken here in the city in November, one of which we know today as “Ultima Thule,” his most famous likenesses. A few days after this photo was taken, Whitman finally agreed to a conditional marriage. The first condition was that he abstain from alcohol. She knew that it was a vice that he struggled with not only throughout his whole life, but already during his brief time in Providence. The second condition was that her mother, Anna Power, had to consent to the union. In order for that condition to be met, Mrs. Power had a condition of her own: Her daughter must forfeit her substantial inheritance in order to marry Poe. Probably much to everybody’s surprise, all these conditions were met. Poe and Whitman planned to marry sometime the following month.

On December 20, 1848, Poe lectured before the Franklin Lyceum at Howard’s Hall, the same venue that initially brought him to Providence in 1845. He spoke on “The Poetic Principle” before a sold-out crowd of 1800 people from all over the state. Whitman sat in the very front row of the auditorium. Spectators who were friends of Whitman and knew of her engagement to Poe later recalled that while Poe recited his works such as “The Raven” and “The Bells,” he exchanged a number of flirtatious expressions with Whitman. The lecture must have impressed her so profoundly that she wished for an immediate wedding.

They planned to wed on Christmas at St. John’s Cathedral, but Whitman’s family and friends detested Poe, strongly discouraging the union. Whitman’s own mother said that she would rather see her daughter dead than with Poe. Poe entrusted the wedding announcement to Whitman’s friend, William Pabodie, to deliver to the Reverend at St. John’s to have it published. Pabodie purposely delayed the delivery of the announcement, and it was never published. It was probably for these reasons that Whitman received an anonymous note while she was with Poe at the Athenaeum just two days before the wedding. The note informed her that Poe had a glass of wine at his hotel and was seen intoxicated. The wedding was called off.

It was at the red house that still stands today on Benefit Street that Poe made his final plea to Whitman. The stress of the matter was so intense that she pressed an ether-soaked handkerchief to her face and fainted on the couch. Poe knelt by her side, tightly gripped her hand, and begged her just to say that she loved him. She uttered one final “I love you” to Poe before slipping out of consciousness. Whitman’s mother then forced Poe out of the house, telling him that he better not miss the next train home.

Poe and Whitman never saw each other again after this, and Poe died less than a year later. Whitman lived another thirty years and became a staunch defender of Poe’s reputation after it was slandered by his literary rival, Rufus Griswold. In 1860, Whitman published a definitive defense of Poe titled Edgar Allan Poe and His Critics, directly refuting Griswold’s lies. She corresponded with Poe’s early biographers, even while she was on her deathbed, ensuring that an accurate portrayal of the man that she loved so many years ago. These action truly attested for Whitman’s moral and beautiful character.

In 1858, Anna Power had passed away, and Sarah Helen Whitman had the sole responsibility of looking after her mentally ill younger sister, Susan Power. In 1862, Whitman and her sister moved from their long-lived home on Benefit Street to a house that was located on Wheaton Street. Their time at that Wheaton Street house was brief. After four years, they moved into a house at 39 Benevolent Street, in 1866. Whitman’s devotion to her sister proved to be quite a weight on her shoulders. Visitors to the house were often turned away due to Susan’s sometimes violent behaviors. Few visitors were able to make it inside the home when Susan was either having a good day, or, when she decided to hide in a closet. Those guests were often in awe by Whitman’s style of decorating. She smothered the walls with mirrors and art, often throwing drapery over lamps in the house to direct the light at her favorite pieces.

They never kept much food in the house, but it was said that they would eat like royalty when they decided to splurge. It was in this house that Whitman hosted literary salons that were attended by some of Providence’s most notable folks, including John Hay. The house also served as a séance parlor where Whitman led many conversations with the dead. On December 8, 1877, Susan passed away in her sister’s arms. Whitman memorialized her in the last poem that she would ever write, titled, “In Memoriam.” The following month, Whitman auctioned off most of her possessions and moved into the home of her friend, Charlotte Dailey. The Daileys were Whitman’s friends and took care of her during the final months of her life. Shortly after Whitman moved into the home in January, 1878, she wrote to her English correspondent, the aspiring Poe biographer, John Henry Ingram: “I am for the present in the beautiful home of the Dailey’s—sitting before a cheerful wood fire in an upper-room looking out on fields and meadows and pleasant gardens.”

Whitman had a generous room in the house with all of her statues and portraits decorated to her liking. She was free to take guests as she pleased and had complete liberty in the home. Charlotte Dailey’s oldest daughter, nicknamed “Lottie,” was especially fond of Whitman, devoting much of her time attending to her. Lottie listened to Whitman recount her life and famous relationship with Edgar Allan Poe, whose portrait hung in Whitman’s room. Whitman would often gaze at the portrait as she recollected her time with him. The Daileys helped Whitman transcribe letters to her correspondents, establish her will, and assisted in compiling an edition of poetry that Whitman planned to have published after her death.

Whitman’s visitors said that her manner was so pleasant, and they heard not one complaint from her during her final days. There was no doubt that Sarah Helen Whitman was fearlessly ready for death, which came for her on June 27, 1878 at half past nine o’clock. Charlotte Dailey and her daughters were at her bedside when she died.

The official cause of death was “affection of the heart, complicated by other ailments.” She was seventy-five years old. Whitman had requested that a formal announcement of her death be sent to the papers after her funeral had already taken place and that no invitations to her services be sent out. While the Daileys honored Whitman’s unusual requests, it did not affect the large turnout of people that showed up to the home on the day of Whitman’s wake. Reposed in the Dailey’s parlor in a casket veiled with white cloth, Whitman was clad in a white dress. Friends said that she looked as beautiful as a bride, even in death. Whitman’s brown hair was scarcely touched with gray. She was surrounded by an array of gorgeous flowers, a wreath of green leaves and ripened wheat adorned the top of her coffin, while her hands pressed a bunch of beautiful and fragrant roses to her chest. The service closed with scriptures read by the secretary of the Women’s Suffrage Association, Anna C. Garlin, who was also Whitman’s close friend. Following the scriptures was a reading of Whitman’s poem, “The Angel of Death.”

Her remains left the home by horse-drawn hearse on route to the North Burial Ground. The funeral procession followed close behind her. When they arrived at the cemetery towards the closing of the afternoon, Whitman’s opened grave awaited her, lined completely with laurel and evergreen so that none of the naked earth could be seen. After Whitman’s casket was lowered, her friends tossed more bunches of greens and each a scatter of flowers upon the closed lid.

Another unusual request that Whitman had made in preparation of her death was that no stone be placed above her remains. She wanted nothing but the green earth to mark her final resting place. The Dailey women could not bring themselves to comply with this one request. The compromise was this modest stone in Whitman’s honor. The Daileys served as her executor, and they were an integral part of ushering Whitman’s legacy to future generations. Sarah Helen Whitman is the prime example of a cherished woman having left the world a bit brighter and more inspired than she found it.

Photo by Levi L. Leland.